Imagine that you just received your ballroom dress ordered from the internet, and the quality is not as promised, the dress doesn't fit you, and it doesn't even look like the one on the picture?. Worst of all – you can't return it.

It’s so easy to make a mistake that can cost you a lot of money and turn your ballroom dance competition into big, costly disappointment. Here are some common mistakes and tips/

Not Knowing Enough About the Dress Company

Before you buy your ballroom dress you should always get all the neccessary information. Here are some questions that you should ask that can save you hundreds of dollars:

1. How exprienced are you, and how long have you been selling dresses on the Internet?

2. Are you making your own dresses, or do you resell??

Buy directly from a dressmaker to save at least 20 to 30%

3. Does anyone in the company has dance exprience ?

You can’t expect professional advice or assistance from someone who does not know anything about dancing or ballroom dresses. Unfortunately there are companies that sell hundreds of dresses, but they don’t have any knowledge or experience in that field. You should especially check if the designer or the person taking your order, is knowledgeable in ballroom dancing costumes.

1. Does the company/ dressmaker guarantees the quality of its work, fabrics and stones?

Buy your ballroom dress only from a company that provides clear quality and fit guarantee and accepts returns in case the dress doesn’t meet your expectations.

3. Choosing a Dress That Would Look Better on Someone Else

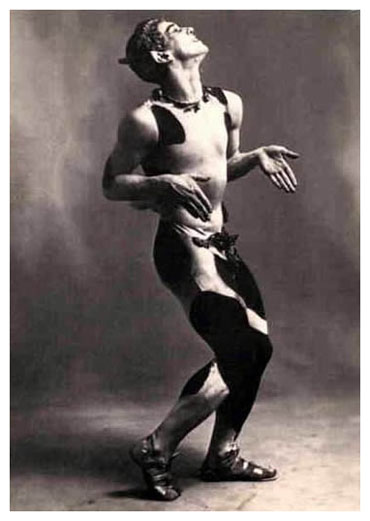

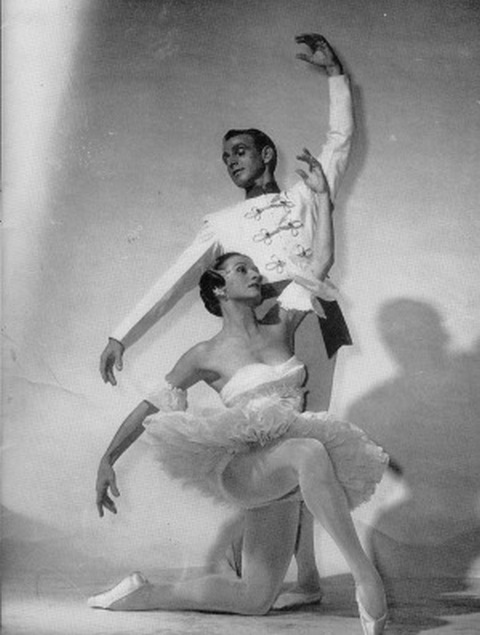

Very often when we watch dance competition and see the dress that is absolutely breathtaking, we fall in love with it instantly. What we don't realize is that the strong impression we had was not just the dress. It was both the dress and dancer( her body shape, skin color, hairstyle, make up) and the dancing (her technical skills, speed, presentation). If you put the same dress on someone else, you will have impression. Wear something that feels and looks right on you as an individual.

4. Buying Cheap, Poor Quality Dresses

4. Buying General Sizes

Many companies that mass produce dresses offer only general sizes like: S, M, L, XL. Those average sizes almost never match a real person measurements. Most women have either a few inches more or less in different parts of the body compare to general sizes.

You might have a good taste for fashion and clothing, but it requires a real experience to choose a dance dress that makes you look really good.

If possible find a professional designer that can work with you to create custom dance dress that is perfect for your body type and your dancing skills. Another idea: Put everything into one design ( 5 different ideas from different dresses)

A Few Handy Saving Tips

It’s so easy to make a mistake that can cost you a lot of money and turn your ballroom dance competition into big, costly disappointment. Here are some common mistakes and tips/

Not Knowing Enough About the Dress Company

Before you buy your ballroom dress you should always get all the neccessary information. Here are some questions that you should ask that can save you hundreds of dollars:

1. How exprienced are you, and how long have you been selling dresses on the Internet?

2. Are you making your own dresses, or do you resell??

Buy directly from a dressmaker to save at least 20 to 30%

3. Does anyone in the company has dance exprience ?

You can’t expect professional advice or assistance from someone who does not know anything about dancing or ballroom dresses. Unfortunately there are companies that sell hundreds of dresses, but they don’t have any knowledge or experience in that field. You should especially check if the designer or the person taking your order, is knowledgeable in ballroom dancing costumes.

4. Are you making dresses for a specific customers, like the European, Asian, North American, or do you take international orders too?

There is a big difference between ballroom dancers from the US and Japan for example. Their mentality, expectations, body type and style of performance are very different. Make sure your dressmaker as experience in making dresses for your particular market.

5. Are you experienced in making dresses for online customers?

These days almost every dressmaker owns a website. But many of them focus on local dancers that come for a fitting. Usually it takes 2 to 3 visits to make sure the dress fits well. So when they take an online order, the customer that is on other side of the world they might struggle getting the dress properly fitted, as they are not used to working with size chart and mannequin alone.

2. Buying With no Guarantee

That is probably the biggest mistake you are likely to make.

That is probably the biggest mistake you are likely to make.

It is in your best interest to check the following:

1. Does the company/ dressmaker guarantees the quality of its work, fabrics and stones?

2. Does the company/ dressmaker guarantees that the dress size will fit you?

3. Do they have a satisfaction guarantee or return policy?

Buy your ballroom dress only from a company that provides clear quality and fit guarantee and accepts returns in case the dress doesn’t meet your expectations.

3. Choosing a Dress That Would Look Better on Someone Else

Very often when we watch dance competition and see the dress that is absolutely breathtaking, we fall in love with it instantly. What we don't realize is that the strong impression we had was not just the dress. It was both the dress and dancer( her body shape, skin color, hairstyle, make up) and the dancing (her technical skills, speed, presentation). If you put the same dress on someone else, you will have impression. Wear something that feels and looks right on you as an individual.

4. Buying Cheap, Poor Quality Dresses

Unfortunately, there is no such a thing as “good quality, cheap ballroom dress” In order to compete on prices some companies are using poor quality fabrics unsuitable for dance costumes, mass producing same design in 100s or even 1000, using general sizes like S, M, L, XL, and hiring unexperienced dressmakers

Many companies are buying cheap, mass produced dresses directly from Chinese factories, and stylizing them as high quality dance gowns. It’s done by sticking few laces on top, putting some sequins and some stones and few pieces of fabric. It may look good on the picture you see on Internet, but the actual ress won't be worth it.

To make a high quality stunning dress you have to use dance costume dedicated, high quality fabrics. They are highly stretchable, to let you move and dance comfortably, and do not wear as easily as regular fabrics to keep the fresh, stunning look for a long time. Dedicated fabric can be even 10 X more expensive then the regular materials. Next are the stones. If you wanna look gorgeous you have to go with famous Swarovski stones. This Austrian company is a real legend and has been making stones for dance costumes for years. You simply can’t beat the sparkle, shine and attention that Swarovski stones draw on the dance floor. They are much more expansive then the other stones. Last but not least is the quality of work. Well and properly made dress will fit like a glove and last.

How you look, and how you feel has a great impact on your performance. Make sure you get the best dress you can afford. Don’t miss your chance of winning by trying to save few bucks.

4. Buying General Sizes

Many companies that mass produce dresses offer only general sizes like: S, M, L, XL. Those average sizes almost never match a real person measurements. Most women have either a few inches more or less in different parts of the body compare to general sizes.

A well fitted dress is very important. If it is too loose or too tight it will completely disturb your dancing. You won’t be able to concentrate and enjoy your performance. Remember that you are not buying an evening dress, that you are going to walk or stand around. You are buying a ballroom dress or a Latin dress that you are going to move, stretch, turn and twist. It’s very important that you feel comfortable wearing it.

Always buy a dress that is well fit to your body, or spend some extra money on tailor to get it adjusted to your body size and shape.

6. Buying Without Professional Advice And Assistance

6. Buying Without Professional Advice And Assistance

You might have a good taste for fashion and clothing, but it requires a real experience to choose a dance dress that makes you look really good.

Well chosen dress will bring attention to the parts of the body that you feel most comfortable about. It will emphasize your strengths as a dancer, and it will hide your weaknesses. For example if you have a strong technique and want to show your leg action in Latin or Rhythm you need dress that will draw attention there. On the other hand if leg lines or foot action is not your strength, you want judges to look somewhere else, maybe at your hands and beautiful smile.

If possible find a professional designer that can work with you to create custom dance dress that is perfect for your body type and your dancing skills. Another idea: Put everything into one design ( 5 different ideas from different dresses)

A Few Handy Saving Tips

- Buy directly from a dress maker not reseller (save 20-40%)

- Buy from an online company that doesn’t have an expensive showroom ( showroom cost usually makes your dress 20 – 30% more expensive)

- Find company that doesn’t charge extra for custom-made dresses and made to measure dresses (save 15-30%)