Frankie Manning (1914–2009) staged and performed numbers across four continents, arranged choreography for seven films and opened for major musical acts like Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Count Basie and Nat King Cole. He made the acquaintance of Queen Elizabeth and won the 1989 Tony Award for his choreography in the musical Black and Blue. His high-spirited dance style has produced fan-favorite swing routines on “So You Think You Can Dance” and “Dancing with the Stars” (he even received a shout-out from “SYTYCD” judge Mary Murphy on Season 6)—but does his name ring a bell? Unless you love Lindy hop, it probably does not.

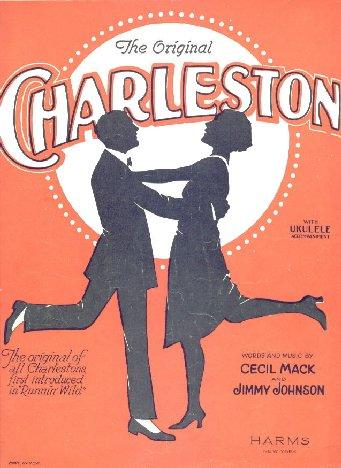

The man with the million-dollar smile who came of age during the Harlem Renaissance should be as familiar as Fred Astaire. But Manning was not driven by fame or money. He was a self-taught dancer enthralled with the Lindy Hop, a hyperkinetic swing dance that evolved at Harlem’s famed Savoy Ballroom during the 1920s and ’30s. His predecessors built Lindy hop from a ragout of social dances, like the black bottom, Charleston, mess around, blues, collegiate and breakaway, all popular when dance clubs and big bands ruled the night. But it was Manning who developed the style-defining air steps (lifts), synchronized routines, sharp angles and low-to-the-ground stance that transformed Lindy hop into a major American ballroom dance craze.

Harlem Beginnings

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Manning moved to Harlem with his mother when he was 3. As a child, he soaked up the dancing done by his mother and friends at house parties, and as a teenager, he discovered Lindy hop at New York City’s Alhambra Ballroom. Around 1933, Manning entered dance competition king Shorty Snowden’s territory—the Savoy Ballroom, ground zero for Lindy hop. (Snowden named the dance in reference to Charles “Lindy” Lindbergh’s 1927 solo “hop” across the Atlantic.) In the Harlem club, the best dancers burned up the floor in an area called “Kat’s Korner.” It was here where Manning’s dancing first gained attention, especially his unique Lindy hop. He projected his upper body forward like a plane taking off, and engaged his partner face to face and at arm’s length, thus giving greater space for improvisation. He danced so hard that the veins bulged across his skull, earning him the nickname Musclehead.

In 1935, Manning and then-partner Frieda Washington unveiled their now-famous aerial step, the “Over-the-Back”—an acrobatic move where one partner’s feet leave the ground completely. As Manning flipped Washington over his head, thrilling the huge crowd, a Savoy bouncer named Herbert “Whitey” White saw gold. Whitey organized Manning and other Lindy hoppers to perform as opening acts at major venues. Upon being contracted to perform for six months at the Cotton Club, Manning realized he had talent and quit his day job as a furrier to dance professionally.

During the next several years, the group toured the world, appearing at Paris’ Moulin Rouge, London’s Palladium, in Australia and New Zealand and at the World’s Fair in New York. Although Manning staged the group’s dances, it was Whitey’s name that identified the troupes—Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, Whyte’s Hopping Maniacs, Whitey Congeroo Dancers. Manning was also the uncredited brains behind the energetic dances in films, including Keep Punching (1939), Hellzapoppin’ (1941) and Killer Diller (1948).

On the Frontline

In 1943 Manning received his draft papers. To his dismay, his commanding officer never submitted Manning’s request for transfer to the Army’s Special Services section for (mostly white) entertainers and he couldn’t join. Manning fought in the South Pacific, earning the rank of sergeant and experiencing “worse prejudice than any other time in my life,” he wrote in his 2007 autobiographyFrankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop.

With the war’s end, Manning returned to dancing, expanding his Lindy routines to include comedy, tap, jazz and Latin steps. At first, the gigs were plentiful, but as public tastes in music changed in the mid 1950s, his style of entertainment fell out of favor and jobs became scarce. With wife Gloria Holloway and two young children at home, Manning hung up his dance shoes and became a clerk at the General Post Office in Manhattan.

A Renewed Spirit

Three decades later, a new generation of dancers became interested in swing, and in 1984, Manning received a phone call from world-renowned swing dancer Erin Stevens, looking for the famous Lindy hopper. Manning told her, “I don’t dance anymore, baby. I just work at the post office.” Stevens, however, persuaded him to improve her partnering skills. The experience led him to teach, which he continued doing for the rest of his life. His playful and encouraging teaching style—heavily based on demonstrations and singing syllables instead of counting phrases—became highly in-demand around the globe.

The swing revival also brought Manning to dance again—and this time he became famous. In 1989, “20/20” profiled him. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater credited his choreography in Opus McShann(1988). Spike Lee hired him to consult on and appear in Malcolm X (1992). The National Endowment for the Arts awarded him two fellowships (1994, 2000). The National Museum of Dance inducted him into its Hall of Fame (2006). And beginning in 1994, Manning’s birthday parties became swing dance extravaganzas, attended by people from all over the world.

Following a year of declining health, Manning died in 2009 at age 94 of complications from pneumonia. The international swing community memorialized him for months. As big bands swung, dancers bent their bodies forward, celebrating Manning’s long, full life by Lindy hopping all night long.

Tribute Video to Frankie Manning

The man with the million-dollar smile who came of age during the Harlem Renaissance should be as familiar as Fred Astaire. But Manning was not driven by fame or money. He was a self-taught dancer enthralled with the Lindy Hop, a hyperkinetic swing dance that evolved at Harlem’s famed Savoy Ballroom during the 1920s and ’30s. His predecessors built Lindy hop from a ragout of social dances, like the black bottom, Charleston, mess around, blues, collegiate and breakaway, all popular when dance clubs and big bands ruled the night. But it was Manning who developed the style-defining air steps (lifts), synchronized routines, sharp angles and low-to-the-ground stance that transformed Lindy hop into a major American ballroom dance craze.

Harlem Beginnings

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Manning moved to Harlem with his mother when he was 3. As a child, he soaked up the dancing done by his mother and friends at house parties, and as a teenager, he discovered Lindy hop at New York City’s Alhambra Ballroom. Around 1933, Manning entered dance competition king Shorty Snowden’s territory—the Savoy Ballroom, ground zero for Lindy hop. (Snowden named the dance in reference to Charles “Lindy” Lindbergh’s 1927 solo “hop” across the Atlantic.) In the Harlem club, the best dancers burned up the floor in an area called “Kat’s Korner.” It was here where Manning’s dancing first gained attention, especially his unique Lindy hop. He projected his upper body forward like a plane taking off, and engaged his partner face to face and at arm’s length, thus giving greater space for improvisation. He danced so hard that the veins bulged across his skull, earning him the nickname Musclehead.

In 1935, Manning and then-partner Frieda Washington unveiled their now-famous aerial step, the “Over-the-Back”—an acrobatic move where one partner’s feet leave the ground completely. As Manning flipped Washington over his head, thrilling the huge crowd, a Savoy bouncer named Herbert “Whitey” White saw gold. Whitey organized Manning and other Lindy hoppers to perform as opening acts at major venues. Upon being contracted to perform for six months at the Cotton Club, Manning realized he had talent and quit his day job as a furrier to dance professionally.

During the next several years, the group toured the world, appearing at Paris’ Moulin Rouge, London’s Palladium, in Australia and New Zealand and at the World’s Fair in New York. Although Manning staged the group’s dances, it was Whitey’s name that identified the troupes—Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, Whyte’s Hopping Maniacs, Whitey Congeroo Dancers. Manning was also the uncredited brains behind the energetic dances in films, including Keep Punching (1939), Hellzapoppin’ (1941) and Killer Diller (1948).

On the Frontline

In 1943 Manning received his draft papers. To his dismay, his commanding officer never submitted Manning’s request for transfer to the Army’s Special Services section for (mostly white) entertainers and he couldn’t join. Manning fought in the South Pacific, earning the rank of sergeant and experiencing “worse prejudice than any other time in my life,” he wrote in his 2007 autobiographyFrankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop.

With the war’s end, Manning returned to dancing, expanding his Lindy routines to include comedy, tap, jazz and Latin steps. At first, the gigs were plentiful, but as public tastes in music changed in the mid 1950s, his style of entertainment fell out of favor and jobs became scarce. With wife Gloria Holloway and two young children at home, Manning hung up his dance shoes and became a clerk at the General Post Office in Manhattan.

A Renewed Spirit

Three decades later, a new generation of dancers became interested in swing, and in 1984, Manning received a phone call from world-renowned swing dancer Erin Stevens, looking for the famous Lindy hopper. Manning told her, “I don’t dance anymore, baby. I just work at the post office.” Stevens, however, persuaded him to improve her partnering skills. The experience led him to teach, which he continued doing for the rest of his life. His playful and encouraging teaching style—heavily based on demonstrations and singing syllables instead of counting phrases—became highly in-demand around the globe.

The swing revival also brought Manning to dance again—and this time he became famous. In 1989, “20/20” profiled him. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater credited his choreography in Opus McShann(1988). Spike Lee hired him to consult on and appear in Malcolm X (1992). The National Endowment for the Arts awarded him two fellowships (1994, 2000). The National Museum of Dance inducted him into its Hall of Fame (2006). And beginning in 1994, Manning’s birthday parties became swing dance extravaganzas, attended by people from all over the world.

Following a year of declining health, Manning died in 2009 at age 94 of complications from pneumonia. The international swing community memorialized him for months. As big bands swung, dancers bent their bodies forward, celebrating Manning’s long, full life by Lindy hopping all night long.